The Things They Left Behind

What do you do with the things they left behind? The things that were their things, and are now your things. The things that were their parents’ things, and maybe their parents’ too, and will be your children’s things, that is, if you have any.

All of it sits and waits for you, a lifetime of stuff. Not only are their possessions biding time until someone comes, but the food left in the refrigerator and cabinets wait too. There’s crumpled paper in the garbage and a full recycling bin of plastic from when the nurses were last present.

My grandma died in the waning days of summer, just a few weeks shy of her 93rd birthday. She died at home, in her apartment on the Upper East Side, with family and hospice care. It was the best way to die one could hope for, I think. I was grateful she was able to do so in her home, with us.

I knew I wanted to come back and photograph her apartment. I wanted to make pictures not only to document it but to try and understand the process of going through someone’s possessions, the clearing out of space after a loved one dies, the stuff of grief.

I think a lot about how spaces shape us, and my grandma’s space–which was my Papa’s too–was such an integral part of shaping me. All of the things in her space are part of its story, each item has its own narrative too.

There’s the giant antique mirror that hangs over the dining room table where I sat and came out to my grandparents one night in college. The mirror has presided over family gatherings there, and at their prior house on Long Island too. My grandma would spend days preparing to host Seders and other meals for extended family and friends under its glint. There are the deep burgundy goblets on the coffee table next to a matching bowl with an engraved Star of David motif I was always entranced by. I’d sit at eye level with them on the floor back when I was at their height, getting lost in their color. I have no idea where they came from because I never asked, and maybe now I’ll never know. There is the set of silver that comes from her mother which I love so much. It’s ornate and has pieces like a lemon fork and a horseradish spoon. It’s a little gay boy’s dream. We always used it for big holidays, although now because they require extra time and care in washing, we don’t. Jewish holidays often fall on weeknights and everyone has to work the next day. My grandma told me she wished she’d had a career while she was a young mother. She had time to prepare and clean up from big holiday meals, with help from folks she hired too. She pulled out all the stops, cooking everything and serving it on her mother’s china, which we haven’t used in some years either. Its floral pattern is beautiful and brings back cozy memories of a larger family when more of our relatives were alive. It makes me think about prescribed gender roles of generations past, how nice it is to make an occasion for a holiday, and how much work it truly takes. As an adult who’s taken on some of her treasured recipes, I now know the effort needed. I always meant to ask my grandma when her mother got the china and silver, and how she was able to afford them. One’s family doesn’t leave Eastern Europe during the pogroms with dishes. I recently found out from my aunt that my great-grandfather’s millinery business afforded them these heirlooms. Now I wonder what we’ll do with them, where we’ll keep them, how we’ll use them, or if they’ll soon be gone too.

There are photos too of course: a wall of family snapshots, portraits, and important lifecycle moments in the hallway by her room, a collage of her with my grandpa through the years that I made with her hanging by her desk where she could easily look at it, and framed photos of her friends, of my mom, dad and aunt, and of my brother and I around the apartment. There’s the photo of her and my grandpa at their wedding, and then the posed portrait of her before college. It has a handwritten note on it to my grandpa, warning him not to get into trouble while she went away to California for her freshman year. They’d just met at Atlantic Beach where my grandpa was a cabana boy and my grandma’s family had a cabana.

There are artworks from places across Asia, Europe, and South America. There’s a world map in the den that pinpoints where she and my grandfather went together, apart, and with their children. My grandparents made it to all 7 continents. When I was young, the map always made me wonder about faraway lands, an inspiration to explore the world myself. The map has old labels like the USSR and Yugoslavia. I think about the garment industry in which my grandfather worked, and how some of the artworks in the apartment came from business trips to visit factories abroad or were gifts from international clients. I think about how after my dad and aunt went to college my grandma began a career as a travel agent, which granted her the opportunity to explore the world, traveling solo as a woman. I think about how these art objects contain stories and pasts of other families too.

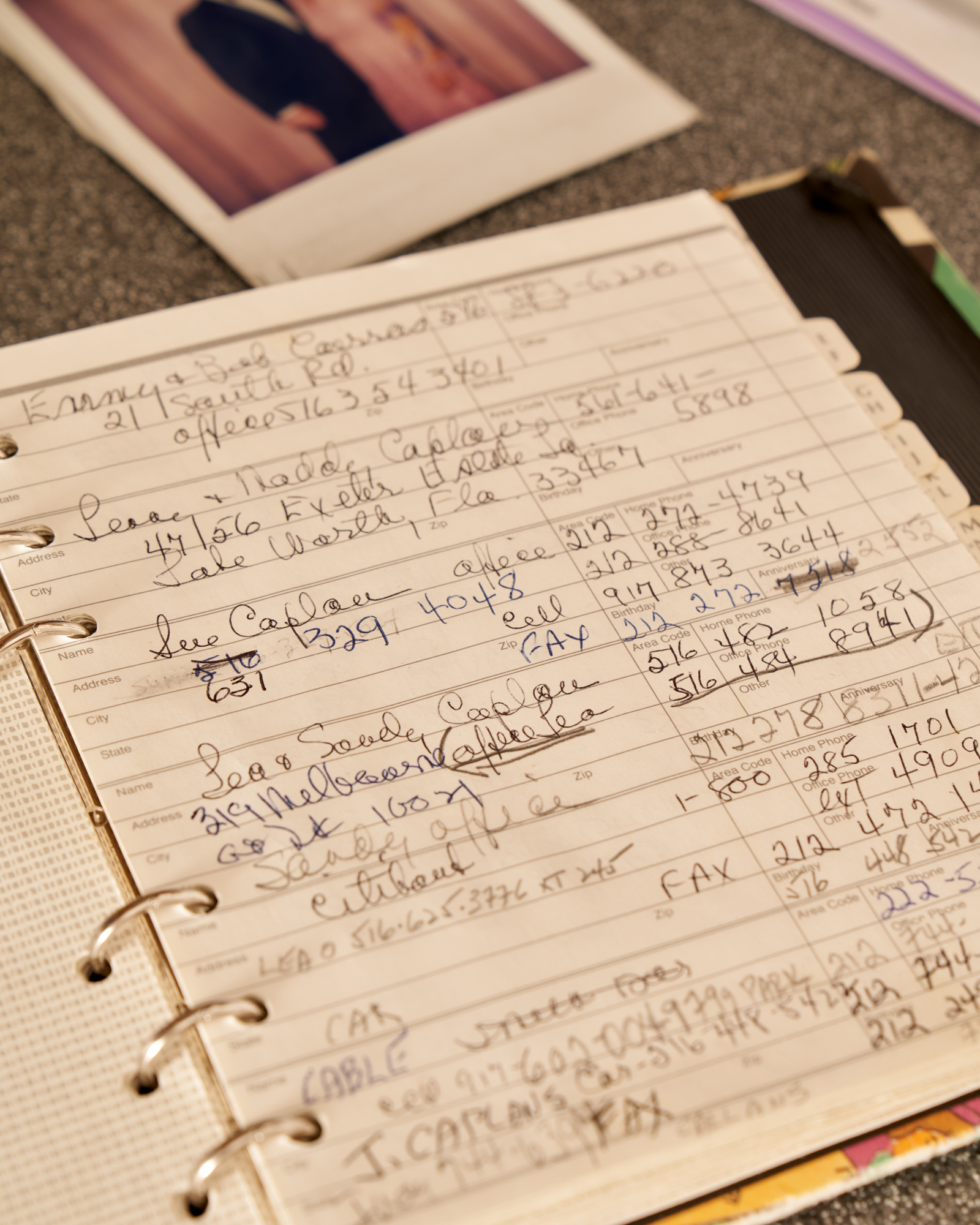

Under the map in the den is a brown couch which replaced the one I used to sleep in. I spent the whole summer after sophomore year in college, and much of the year after college there too. I’d come in late at night after my shift as a gay bar cocktail server before waking up to paint walls as an intern at MoMA PS1. By the window is my grandma’s computer where she sat to check emails, organize papers, and make calls. She was diagnosed with dementia right before the pandemic. I set us up to attend virtual programming for people with memory loss at the arts institutions she loved and frequented. She’d sit there at her computer, and I’d sit at mine in Brooklyn to join classes together during the lockdown. It was almost as nice as how we’d explored museums together in person. Around her desk are booklets of memory exercises and a large print calendar that was easier for her to see. It kept her doctors’ appointments, aide schedules, and physical therapy organized. Her stacks of meticulously arranged tax and business records no longer on their shelves, now sit in bags on the floor, waiting.

The first time I went to her apartment to try and make some photographs was about six weeks after her funeral. I felt like I was ready. I made it uptown with my photo gear and the doorman let me in. It was quiet. There was no classical music from QXR on the speakers, nor news on the TV like usual, just the faint sound of cars below. The first thing I noticed when I walked in were handwritten cards from her aides, family, and friends peeking out of a favorite bowl on the credenza. I froze, dropped my bags, sat on the floor, and cried. I didn’t make any good photos that day. The space overwhelmed me. I didn’t realize how hard it would be to be there. The apartment was full of her presence and empty of it too. It sunk in that she’d never be back. I ended up cleaning out the refrigerator and tossing the trash in what she called the ‘disappearing room.’ I packed the unopened boxes of her favorite granola to bring home. It seemed sad to let them go to waste, but also weird to eat them. While I was driving home to Brooklyn on the FDR, a car cut off an ambulance behind me, side-swiping me in the process, leaving me stranded to change a flat in the middle of the highway while cordoned off by some police cars. Back at home, I sat at my dining table, and ate her granola.

I finally went back that February, after the car was repaired, and after I’d had more time. It’s amazing how things don’t move when there isn’t anyone to move them. I went to my aunt’s apartment to pick up my grandma’s jewelry they’d taken away for my cousin to organize and catalog. I wanted to put it back in the drawer where she’d kept it and photograph it in the space where it lived. The photograph though is only my own approximation, the image itself becoming a new memory since the way she’d kept it is lost. That day at her apartment went better than my first try. Everything still hurt, but it also felt ok. I carried my camera through each room as if to say goodbye before we as a family started to really go through it all. The photographs from that day are neither a before, nor fully an after, but somewhere in between. They’re in between how she last had things, and how things moved for her death. They’re images of a limbo before things get wrapped up, ready for their new destinations. Most of the photos I took that day are with things as I found them, but the photos of her bed I staged too. It was disassembled and moved so a hospital bed could be brought in for her hospice care. I didn’t want to photograph her room like that though. The doormen were kind to put the bed back together, and her aide washed the sheets, which I then ironed and put back over the mattress. It’s not exactly how she had it, but it’s close. Soon though the bed will be gone again, along with all the other things in her apartment. They will be dispersed among family members, donated, or sold. The rest will be thrown away.

All of it sits and waits for you, a lifetime of stuff. Not only are their possessions biding time until someone comes, but the food left in the refrigerator and cabinets wait too. There’s crumpled paper in the garbage and a full recycling bin of plastic from when the nurses were last present.

My grandma died in the waning days of summer, just a few weeks shy of her 93rd birthday. She died at home, in her apartment on the Upper East Side, with family and hospice care. It was the best way to die one could hope for, I think. I was grateful she was able to do so in her home, with us.

I knew I wanted to come back and photograph her apartment. I wanted to make pictures not only to document it but to try and understand the process of going through someone’s possessions, the clearing out of space after a loved one dies, the stuff of grief.

I think a lot about how spaces shape us, and my grandma’s space–which was my Papa’s too–was such an integral part of shaping me. All of the things in her space are part of its story, each item has its own narrative too.

There’s the giant antique mirror that hangs over the dining room table where I sat and came out to my grandparents one night in college. The mirror has presided over family gatherings there, and at their prior house on Long Island too. My grandma would spend days preparing to host Seders and other meals for extended family and friends under its glint. There are the deep burgundy goblets on the coffee table next to a matching bowl with an engraved Star of David motif I was always entranced by. I’d sit at eye level with them on the floor back when I was at their height, getting lost in their color. I have no idea where they came from because I never asked, and maybe now I’ll never know. There is the set of silver that comes from her mother which I love so much. It’s ornate and has pieces like a lemon fork and a horseradish spoon. It’s a little gay boy’s dream. We always used it for big holidays, although now because they require extra time and care in washing, we don’t. Jewish holidays often fall on weeknights and everyone has to work the next day. My grandma told me she wished she’d had a career while she was a young mother. She had time to prepare and clean up from big holiday meals, with help from folks she hired too. She pulled out all the stops, cooking everything and serving it on her mother’s china, which we haven’t used in some years either. Its floral pattern is beautiful and brings back cozy memories of a larger family when more of our relatives were alive. It makes me think about prescribed gender roles of generations past, how nice it is to make an occasion for a holiday, and how much work it truly takes. As an adult who’s taken on some of her treasured recipes, I now know the effort needed. I always meant to ask my grandma when her mother got the china and silver, and how she was able to afford them. One’s family doesn’t leave Eastern Europe during the pogroms with dishes. I recently found out from my aunt that my great-grandfather’s millinery business afforded them these heirlooms. Now I wonder what we’ll do with them, where we’ll keep them, how we’ll use them, or if they’ll soon be gone too.

There are photos too of course: a wall of family snapshots, portraits, and important lifecycle moments in the hallway by her room, a collage of her with my grandpa through the years that I made with her hanging by her desk where she could easily look at it, and framed photos of her friends, of my mom, dad and aunt, and of my brother and I around the apartment. There’s the photo of her and my grandpa at their wedding, and then the posed portrait of her before college. It has a handwritten note on it to my grandpa, warning him not to get into trouble while she went away to California for her freshman year. They’d just met at Atlantic Beach where my grandpa was a cabana boy and my grandma’s family had a cabana.

There are artworks from places across Asia, Europe, and South America. There’s a world map in the den that pinpoints where she and my grandfather went together, apart, and with their children. My grandparents made it to all 7 continents. When I was young, the map always made me wonder about faraway lands, an inspiration to explore the world myself. The map has old labels like the USSR and Yugoslavia. I think about the garment industry in which my grandfather worked, and how some of the artworks in the apartment came from business trips to visit factories abroad or were gifts from international clients. I think about how after my dad and aunt went to college my grandma began a career as a travel agent, which granted her the opportunity to explore the world, traveling solo as a woman. I think about how these art objects contain stories and pasts of other families too.

Under the map in the den is a brown couch which replaced the one I used to sleep in. I spent the whole summer after sophomore year in college, and much of the year after college there too. I’d come in late at night after my shift as a gay bar cocktail server before waking up to paint walls as an intern at MoMA PS1. By the window is my grandma’s computer where she sat to check emails, organize papers, and make calls. She was diagnosed with dementia right before the pandemic. I set us up to attend virtual programming for people with memory loss at the arts institutions she loved and frequented. She’d sit there at her computer, and I’d sit at mine in Brooklyn to join classes together during the lockdown. It was almost as nice as how we’d explored museums together in person. Around her desk are booklets of memory exercises and a large print calendar that was easier for her to see. It kept her doctors’ appointments, aide schedules, and physical therapy organized. Her stacks of meticulously arranged tax and business records no longer on their shelves, now sit in bags on the floor, waiting.

The first time I went to her apartment to try and make some photographs was about six weeks after her funeral. I felt like I was ready. I made it uptown with my photo gear and the doorman let me in. It was quiet. There was no classical music from QXR on the speakers, nor news on the TV like usual, just the faint sound of cars below. The first thing I noticed when I walked in were handwritten cards from her aides, family, and friends peeking out of a favorite bowl on the credenza. I froze, dropped my bags, sat on the floor, and cried. I didn’t make any good photos that day. The space overwhelmed me. I didn’t realize how hard it would be to be there. The apartment was full of her presence and empty of it too. It sunk in that she’d never be back. I ended up cleaning out the refrigerator and tossing the trash in what she called the ‘disappearing room.’ I packed the unopened boxes of her favorite granola to bring home. It seemed sad to let them go to waste, but also weird to eat them. While I was driving home to Brooklyn on the FDR, a car cut off an ambulance behind me, side-swiping me in the process, leaving me stranded to change a flat in the middle of the highway while cordoned off by some police cars. Back at home, I sat at my dining table, and ate her granola.

I finally went back that February, after the car was repaired, and after I’d had more time. It’s amazing how things don’t move when there isn’t anyone to move them. I went to my aunt’s apartment to pick up my grandma’s jewelry they’d taken away for my cousin to organize and catalog. I wanted to put it back in the drawer where she’d kept it and photograph it in the space where it lived. The photograph though is only my own approximation, the image itself becoming a new memory since the way she’d kept it is lost. That day at her apartment went better than my first try. Everything still hurt, but it also felt ok. I carried my camera through each room as if to say goodbye before we as a family started to really go through it all. The photographs from that day are neither a before, nor fully an after, but somewhere in between. They’re in between how she last had things, and how things moved for her death. They’re images of a limbo before things get wrapped up, ready for their new destinations. Most of the photos I took that day are with things as I found them, but the photos of her bed I staged too. It was disassembled and moved so a hospital bed could be brought in for her hospice care. I didn’t want to photograph her room like that though. The doormen were kind to put the bed back together, and her aide washed the sheets, which I then ironed and put back over the mattress. It’s not exactly how she had it, but it’s close. Soon though the bed will be gone again, along with all the other things in her apartment. They will be dispersed among family members, donated, or sold. The rest will be thrown away.